Deleuze for developers: deterritorialization

Home Blog2012-12-07

If you truly want to understand technology today, then you should at least be familiar with the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze. Unfortunately for technologists, Deleuze is rooted firmly in a philosophical tradition and a writing style that they probably find opaque. In this blog series, I plan on explaining Deleuze’s philosophy in terms that programmers can understand. This is the second in the series. You can find the first here, and the next one here. Enjoy.

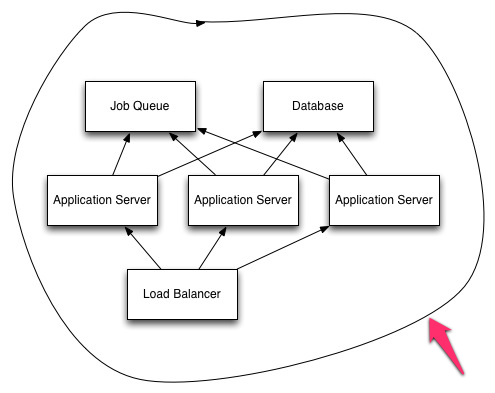

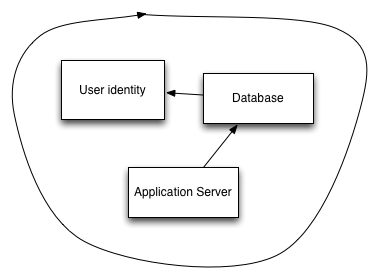

Let’s re-examine this diagram of the assemblage:

What’s up with this line?

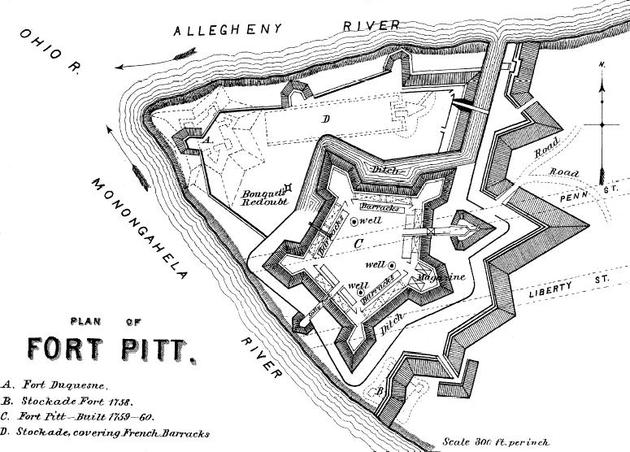

Well, just because assemblages are amorphous doesn’t mean that there’s no way to demarcate what’s in the assemblage and what is not. This particular assemblage has a ‘territory,’ of sorts: everything that’s inside the line is part of the territory, and everything that’s not is outside. Think of a fort, or a castle:

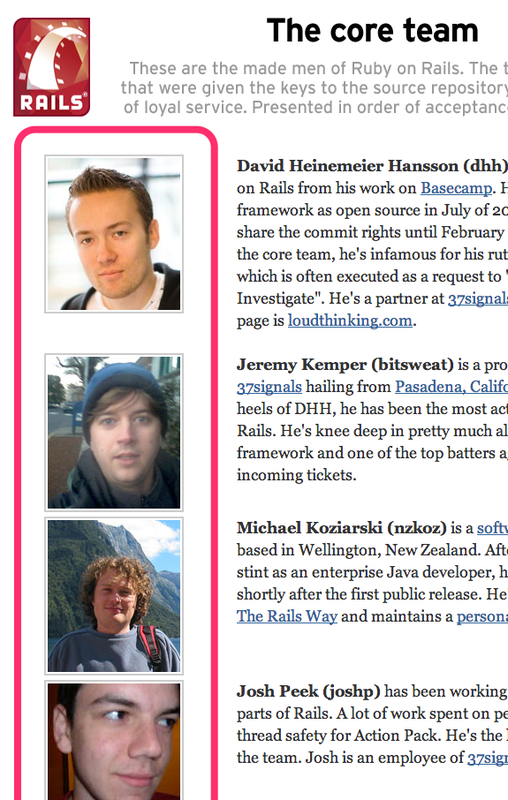

Or, since we’re not just talking about physical spaces, a social circle or group:

Of course, this would extend around all the members of Rails Core, hence it being cut off at the bottom. But the pink line would designate the boundaries of the assemblage that makes up Rails Core.

Deterritorialization

So what happens when these boundaries get crossed? Well, your castle gets invaded. A new member joins the team. New servers are brought online. This process is called ‘deterritorialization.’ Healing the lines, repairing them, and re-containing the boundary is called ‘reterritorialization.’ I recently came across a really interesting symbol of deterritorialization: the Open Source logo:

Check it out: visually, this logo communicates the deterritorializing effect of opening up your source code: the private internals have now been exposed internally. The walls have been breeched!

Another example, from building a web service: we start off with just our service:

We have here an application server, a database, and our user’s identity. They form the assemblage of our system. Remember, abstract concepts are objects just as code and servers are! Our identity notion is stored within the database, therefore, they’re connected.

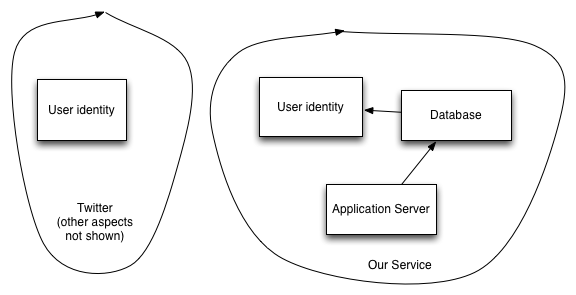

Next, we decide to implement a ‘log in with Twitter’ feature.

It’s the primary way that our users sign up and use our site. Now, Twitter’s assemblage has deterritorialized ours:

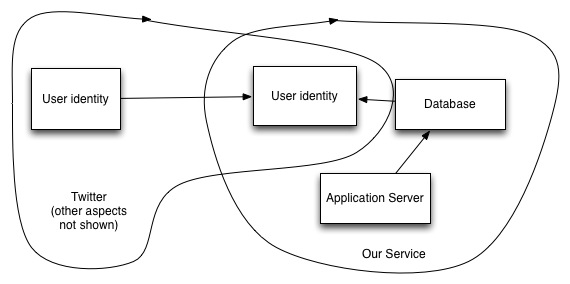

We can minimize the effects (or reterritorialize our service) by making sure to have our own concept of identity within the system, and making sure that we have our own notion of identity within the system, and just connecting Twitter’s notion of identity to our own:

Now, by containing the Twitter-assemblage entirely within our service, I don’t mean that it actually is. Obviously, the Twitter-assemblage is interconnected with a ton of other assemblages that represent other services. But from our perspective, they are now a part of our assemblage. The decisions they make affect us. While our code is separated, we’re not totally separate anymore: updates and policies of Twitter have a direct effect on us.

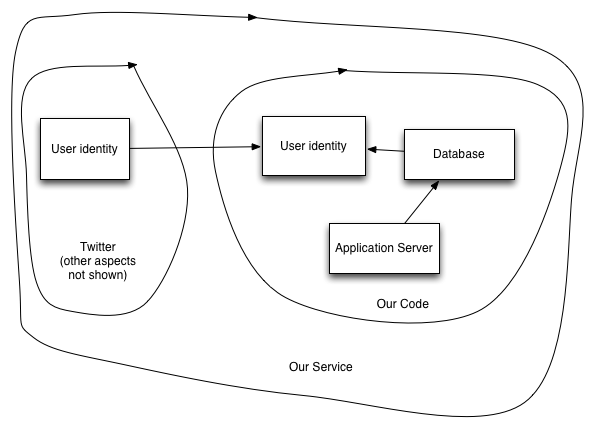

There’s also a more sublte, secondary re/de-territorialization going on here: our code from our service. These used to be isomorphic, but now our code has claimed a territory of its own, and is now just one assemblage within our system-assemblage, instead of being our system-assemblage.

A git example

The previous notion of deterritorialization largely relied on the notion of dependencies as the mechanism which we drew our diagrams. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Let’s take another example: git.

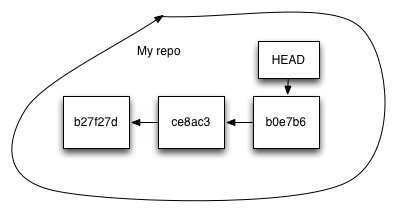

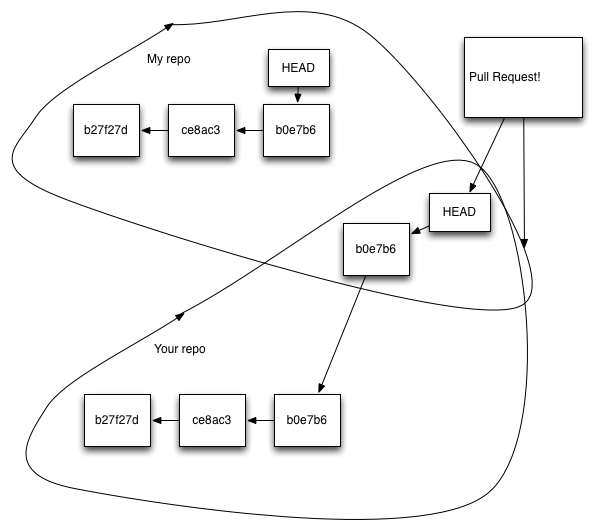

Every GitHub pull request is an act of deterritorialization, and every merge is one of re-territorialization. Consider this small repository, with three commits:

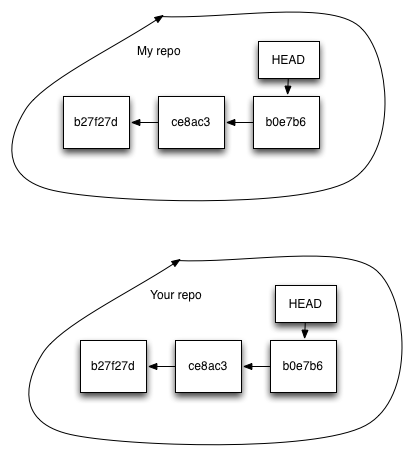

You do a git clone:

Make a new commit, adding a new object into your repo-assemblage:

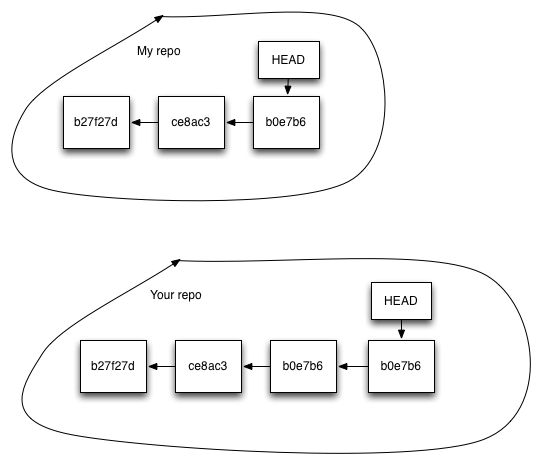

Then you send me an email, asking me to pull from your repository:

You like the change, so you do a git fetch:

de-territorialized!

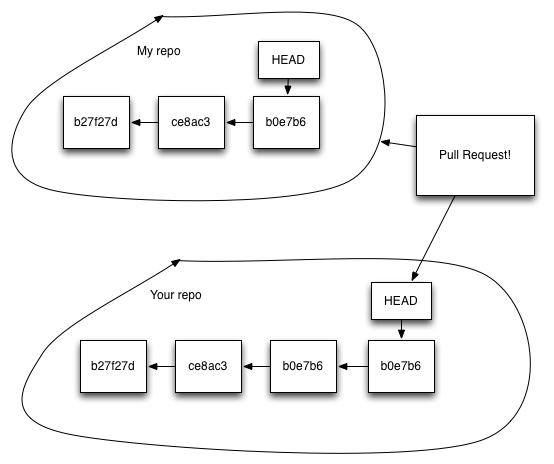

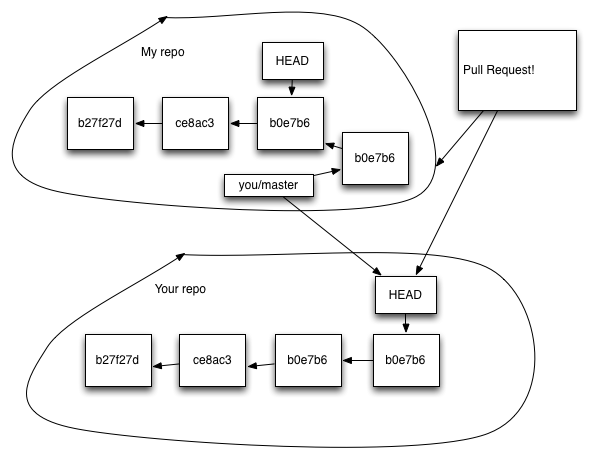

Now it makes the local copy:

and your repository has been re-territorialized. These steps happen so quickly that you probably don’t even think about them, but conceptually, this is what’s happening.

A social example

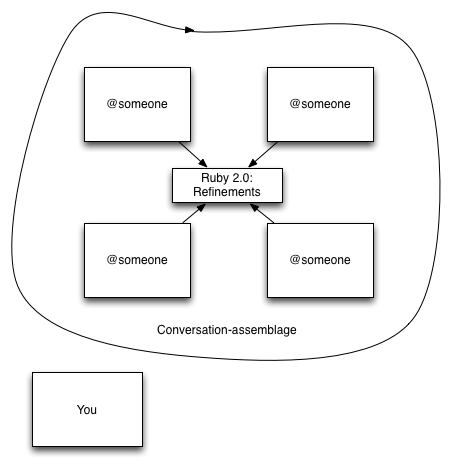

One last example that’s even less related to code: entering a new social group. You’re at a conference, and there are four people standing around talking:

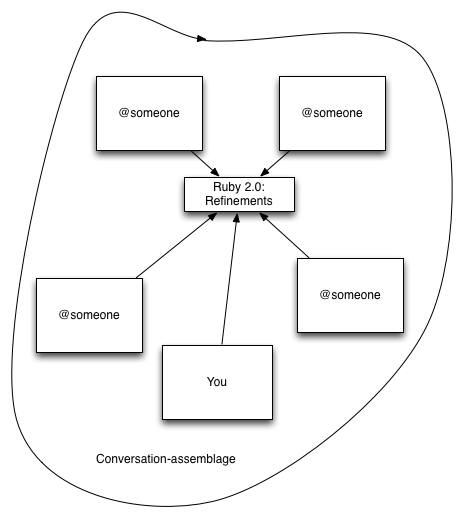

They form an assemblage we call a ‘conversation.’ It’s in relation with an object known as “refinements” from Ruby 2.0, which means this assemblage is likely to be particularly vibrant. Heh. Anyway, you decide that your opinion matters, so you de-territorialize the assemblage, and (assuming they don’t ignore you) it re-territorializes around you:

Even the language we use here implies something similar: you ‘enter the conversation.’ Like entering a door, into a space you previously were not.

Conclusion: Diagrams

We can call these drawings ‘diagrams’ or ‘abstract machines.’ They can represent these kinds of conceptual relationships in a visual way, which I find really useful for understanding. Programmers call abstract machines ‘design patterns.’

Now that you’ve seen this process that assemblages use to relate to one another, I hope that you find this particular diagram useful. Because of its level of abstraction, it’s applicable in a wide variety of situations.